You make a lot of decisions every day. Some big and some small. Some have significant consequences, and some have little impact. No matter what type of decision you are facing, it is imperative to develop a decision process that improves your decision quality and helps sort your choices to identify which ones are more important and which ones are less important.

In her book "How To Decide," Annie Duke presents a framework that helps you make decisions. This article is a summary of the decision-making framework detailed in her book.

For a piece of background information, Annie Duke is a former professional poker player and author in cognitive-behavioral decision science and decision education. Duke's total lifetime live tournament winnings of $4,270,548 place her at fourth overall in the women's all-time live tournament winnings.

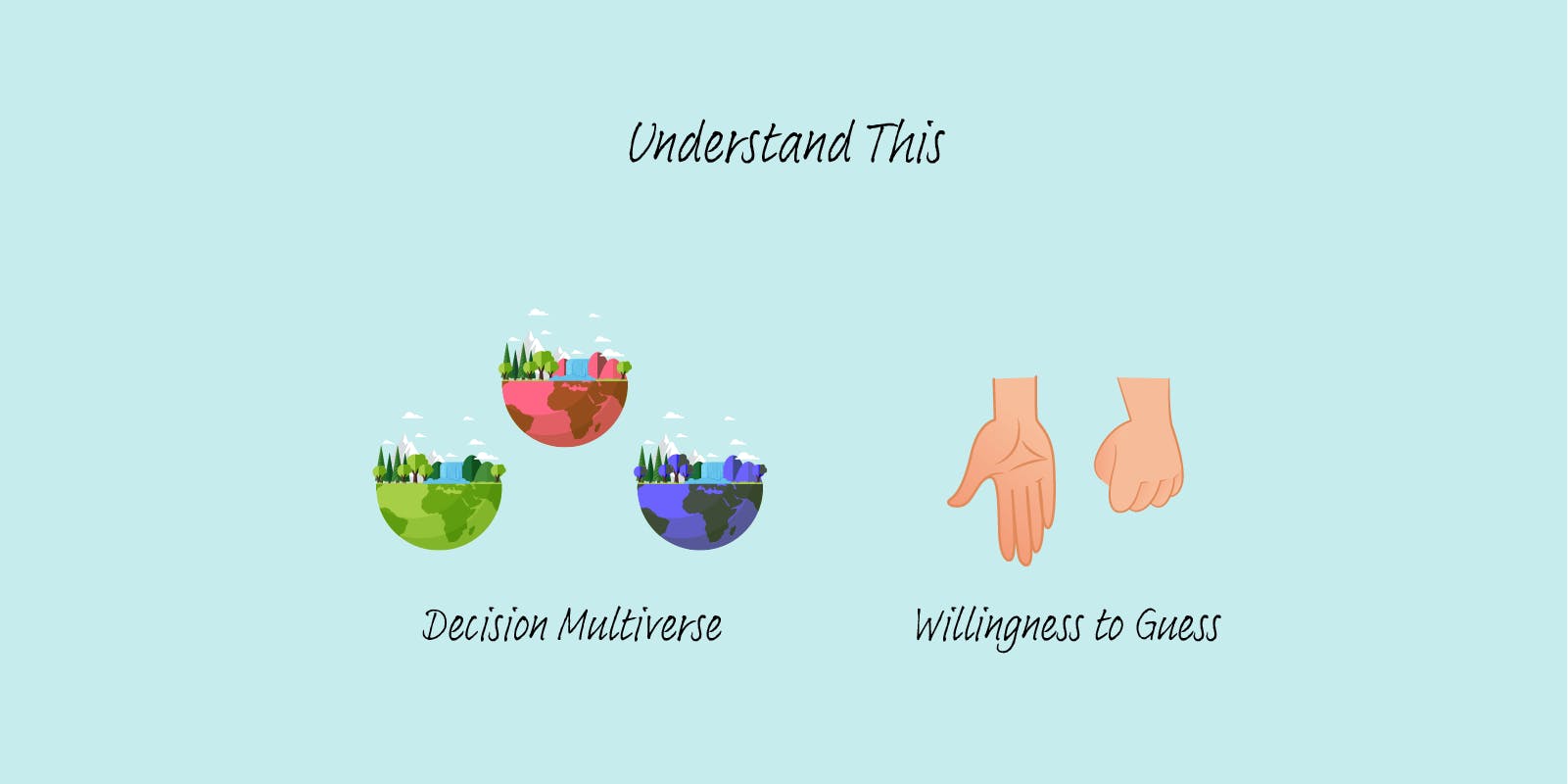

Things to Understand

Decision Multiverse

There are many possible futures. When you make a decision, you see the future possibilities like the branches of a tree, each branch representing how things could unfold. To be a better decision-maker, you need to learn to put possible outcomes (good or bad) in perspective.

Willingness to guess

Most people are reluctant to estimate the likelihood of something happening in the future. ("That's speculative." "I don't know enough." "I'd just be guessing.”). Even though your information is usually imperfect, you know something about most things, enough to make an educated guess.

The willingness to guess is essential to improving decisions. If you don't make yourself guess, you'll be less likely to ask, "What do I know?" and "What don't I know?"

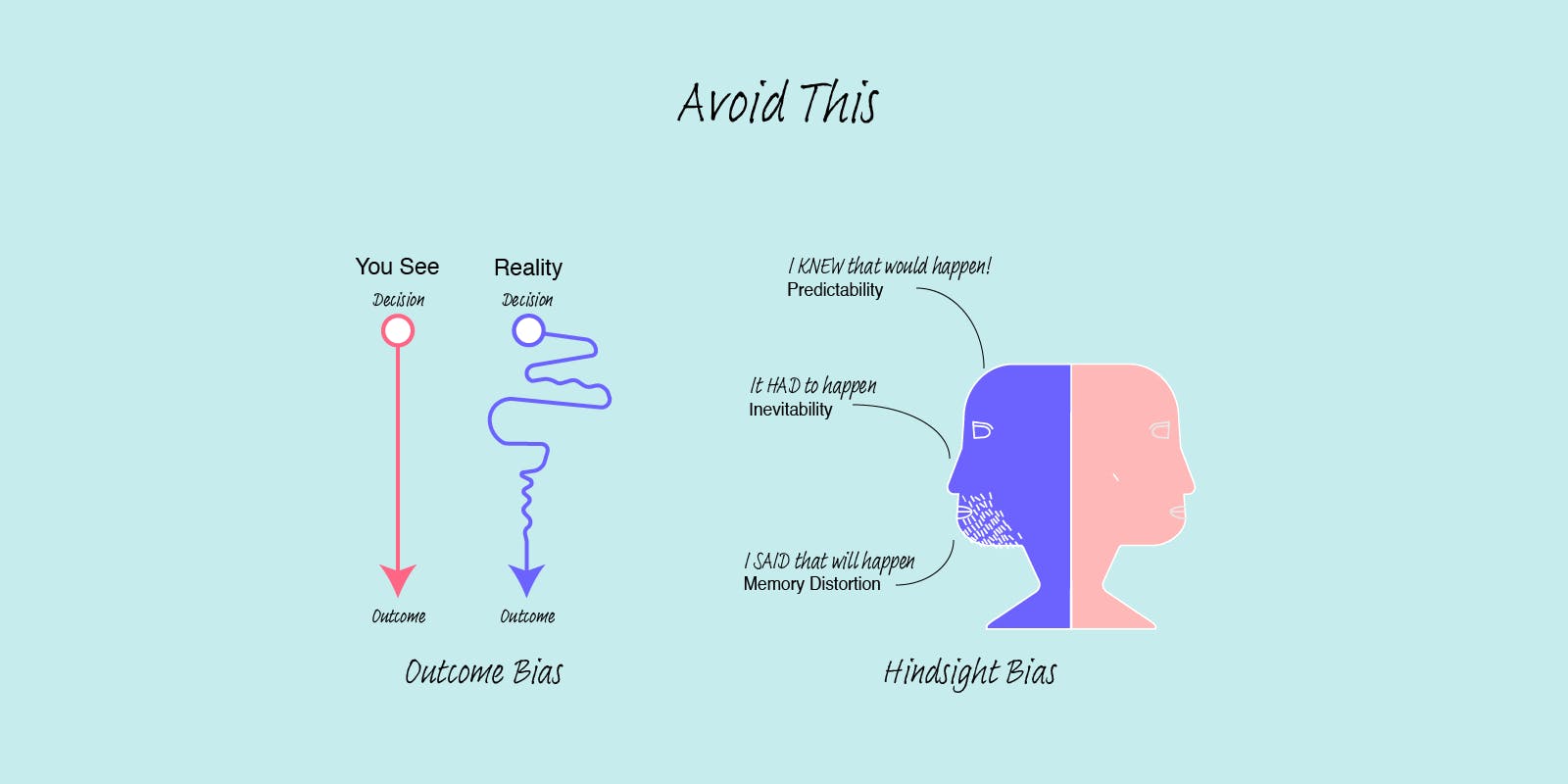

Things to Avoid

Outcome Bias

Outcome bias is a mental shortcut in which we use the quality of an outcome to figure out the quality of a decision. It is the tendency to look at whether a result was good or bad to figure out whether a decision was good or bad.

You should not judge if a decision is good or bad based on the result. There is only a loose relationship between the quality of the decision and the quality of the outcome. When we decide in real life, there is an element of luck. Luck intervenes between your decision and the actual outcome. You can make a good decision and have a bad result due to luck. You can also make a super dumb decision that has a good result.

Hindsight Bias

Hindsight bias is the tendency to believe that an outcome is predictable or inevitable after it occurs. To get better at making decisions, you need to learn from your choices and their outcomes, but hindsight bias distorts the way you process outcomes.

Once you know how a decision turns out, you can experience memory creep, where the stuff that reveals itself after the fact creeps into your memory of what you knew or was knowable before the decision.

Decision-Making Framework

The Three Ps

Preference

There is a greater liking for one alternative over another for every outcome you identified. This liking or preference is individual to you and depends on your goals and values. How much you prefer a particular result relative to other possibilities will naturally be different from another person's preference for the same outcome relative to other possibilities. That doesn't make either of you wrong. It just means that you are different people with particular likes and dislikes.

Payoffs

For any set of outcomes, there will be stuff you could gain (upside potential) and stuff you could lose (downside potential). These gains or losses are called payoffs. Payoffs can be measured in anything you value, like money, time, happiness, health, etc. They will drive your preference because you will prefer gains over losses. When you are figuring out whether a decision is good or bad, you are comparing the upside vs. downside. Does the upside potential compensate for the risk of the downside potential?

Probabilities

Probabilities express how likely something is to occur. To figure out if a decision is good or bad, you need to know the likelihood of each possible outcome.

Without information about the probability of any possibility unfolding, you can beat yourself up over a bad result because you can not see that the result was improbable to happen in the first place.

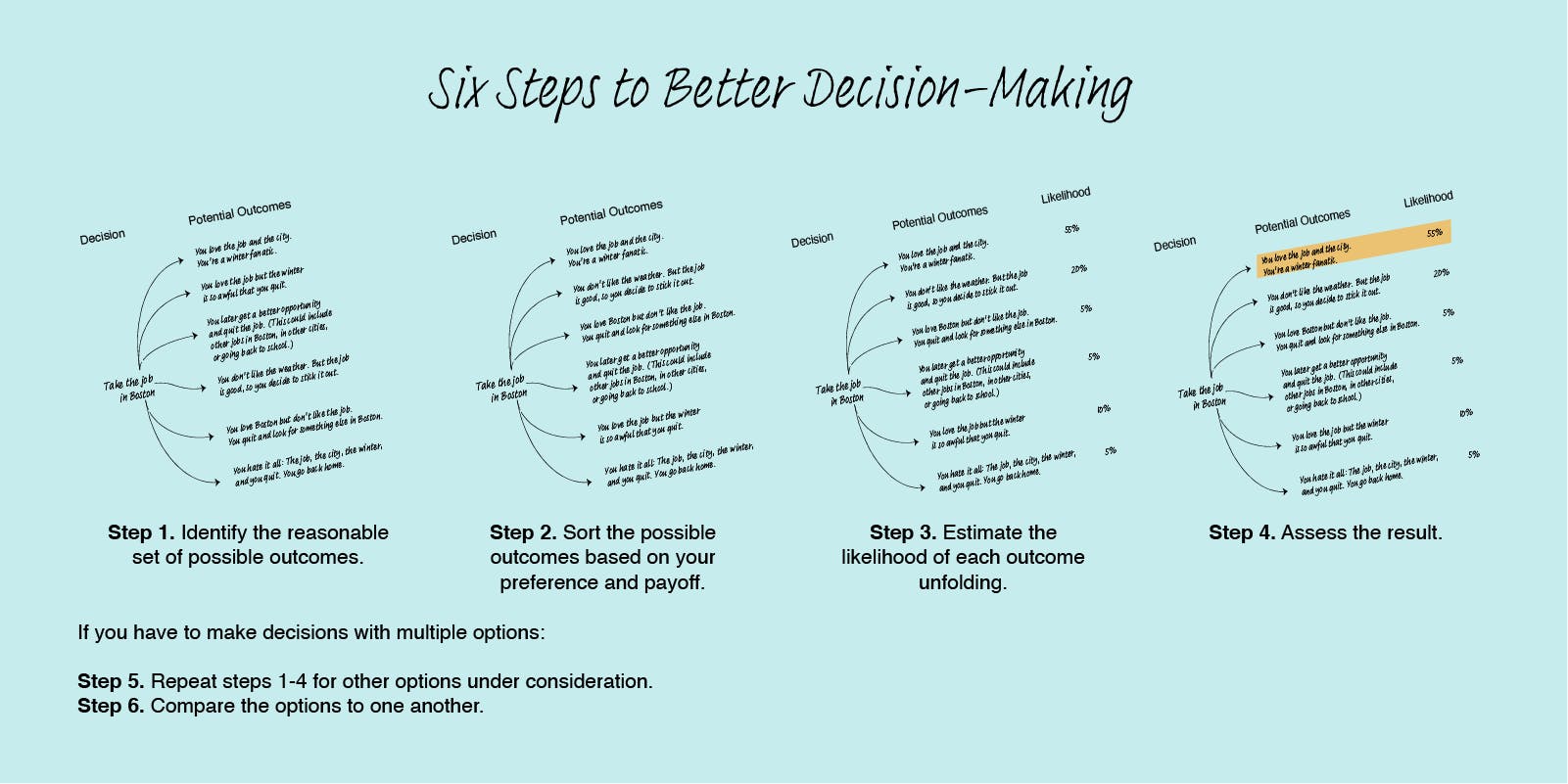

Six steps to better decision-making

- Identify the reasonable set of possible outcomes

- Identify your preference using the payoff for each outcome-- to what degree do you like or dislike each outcome, given your values

- Estimate the likelihood of each outcome unfolding

- Assess the relative likelihood of outcomes you like and dislike for the option under consideration

- Repeat steps 1-4 for other options under consideration.

- Compare the options to one another

How to Spend Decision-Making Time Wisely

The average person spends 250–275 hours per year deciding what to eat, watch, and wear. We take too much time when we make decisions. And many of those decisions we take are routine inconsequential decisions.

When making any decisions, we are faced with a trade-off. Increasing accuracy costs time. Saving time costs accuracy.

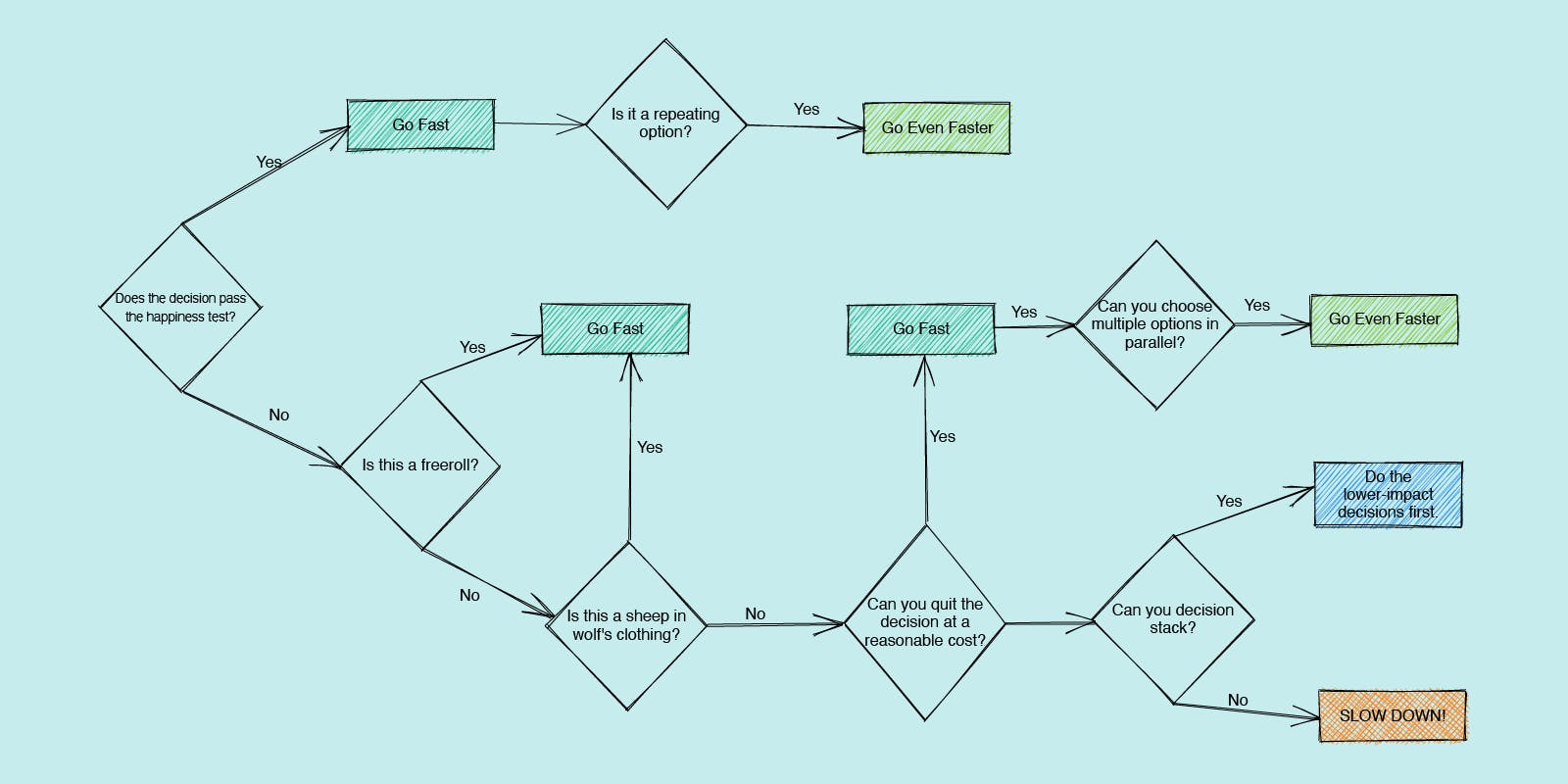

The key to balancing this trade-off is to figure out the penalty for not getting the decision exactly right. When you are making decisions consider these four scenarios.

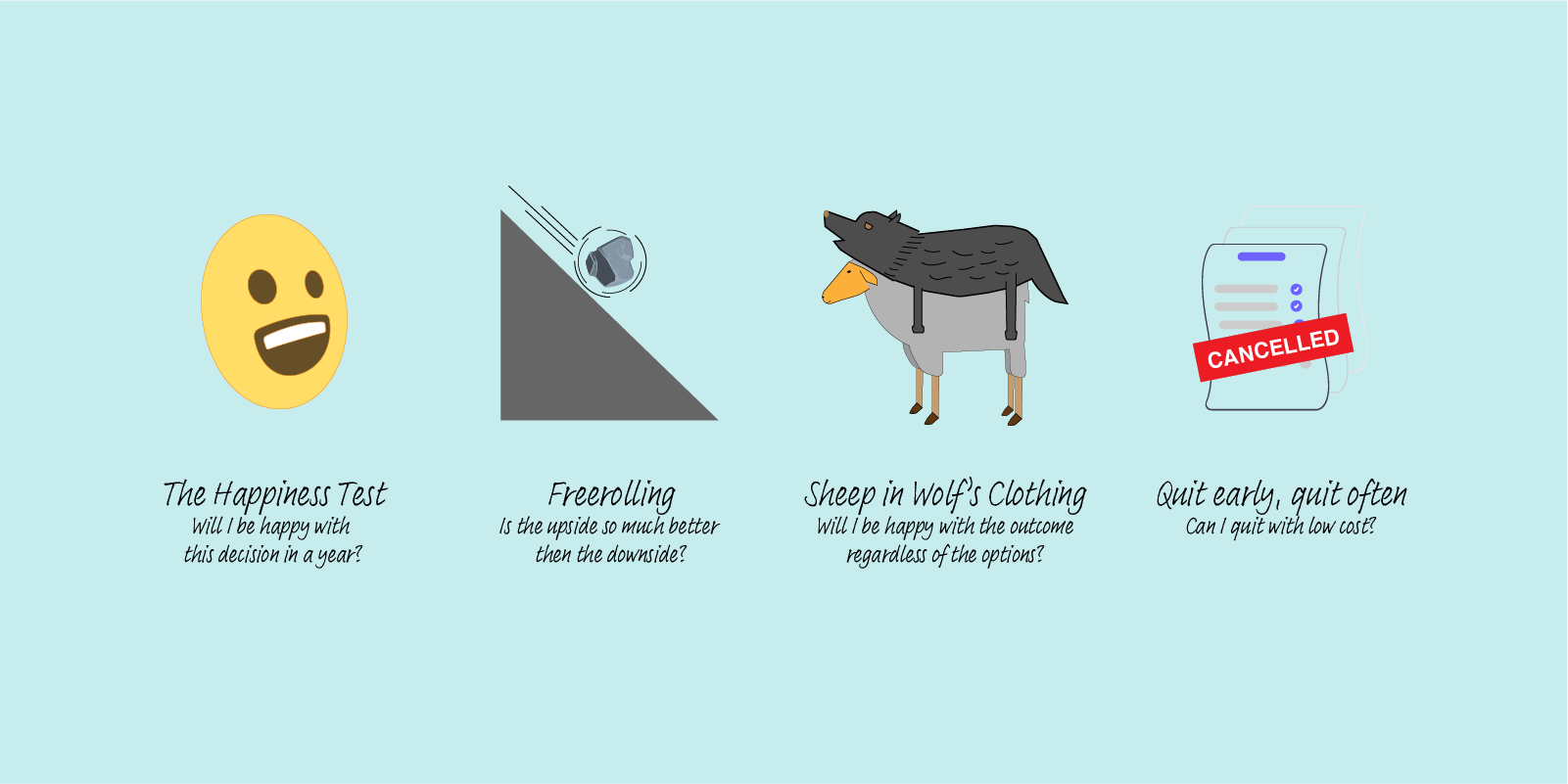

Happiness Test

If the outcome of your decision, good or bad, has no effect on your happiness in a year, you have passed the happiness test, and you can speed up.

Freerolling

When you face a situation where the upside is positive, and the downside is limited, go fast. The faster you decide to seize the opportunity, the quicker you realize the one-sided upside potential of the decision.

Sheep in wolf's clothing

When you are considering two options that are close, then the decision is easy. Whichever one you choose, you can't be wrong since the difference between the two is so tiny.

Quit early, quit often

The lower the cost to quit, the faster you can go because it is easier to unwind the decision and choose a different option, including options you may have rejected in the past.

Decisions with a low cost to quit, known as two-way-door decisions, also provide you with low-cost opportunities to make experimental decisions to gather information and learn about your values and preferences for future decisions.

When facing a decision with a high or prohibitive cost of changing your mind, try decision stacking, making two-way-door decisions ahead of the one-way-door decision. You can also defray opportunity costs by exercising multiple options in parallel.

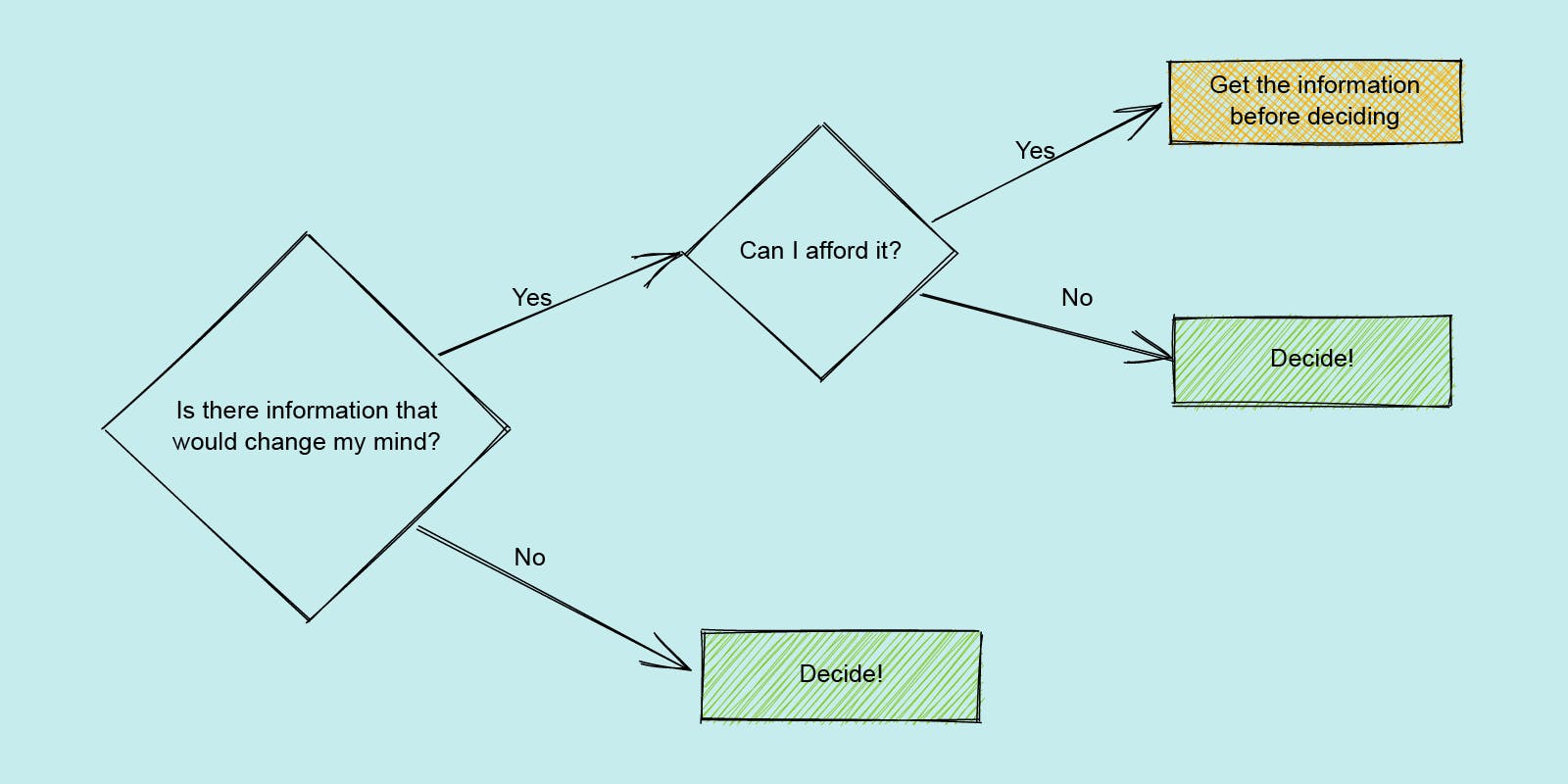

Here is a simple flow chart on how to manage the time-accuracy trade-off.

Knowing When Your Decision Process Is Finished

Because you can not be sure of the outcome of your decision, you will make most decisions while still uncertain. To know if it is worthwhile to have additional time to decide, ask yourself, "Is there additional information (available at a reasonable cost) that would change your mind?" If yes, find it. If no, decide and move on.